Conventional Economic Theory teaches that a government can only spend what it taxes from its population, or what it borrows. Borrowing, of course, must be repaid, either by the generation that does the borrowing or by their children or grandchildren, according to this Theory.

When the national debt is not paid off, or even paid down, but instead continues to grow, conventional economists begin to compare the national debt to gross domestic product, and make dire predictions about what will happen if the debt reaches this percentage, or that percentage, of GDP.

Those economists, and the politicians who subscribe to their theories, then demand that serious measures be taken to reduce the national debt (or, at least, halt its growth) by balancing the government’s budget.

Most people agree with the concept of balancing the budget (so long as the balancing is done on someone else’s back, and not on their own), because they sense a strong similarity between a nation’s ever-growing debt on the one hand, and an individual’s ever-growing debt on the other hand.

This apparent similarity implies that what cannot work long-term for an individual, likewise cannot work long-term for a nation.

Modern Monetary Theory (1) disputes the conventional theories of debt and deficits, (2) contends that the apparent similarity between the budget of a nation and the budget of an individual or household is a flawed similarity, and (3) suggests that nations balance their budgets at their peril.

One of the currently-popular teachers of Modern Monetary Theory, Professor Stephanie Kelton

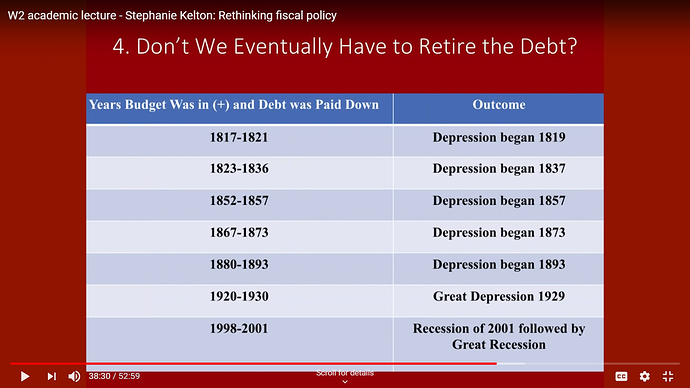

of Stony Brook University, presented the following chart in one of her lectures in early 2019.

She was in Week 2 of her lecture series, Rethinking Fiscal Policy, at UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose in Britain. The chart she presented shows seven attempts by the U.S. government, over the past 200 years, to pay down debt by running a federal government surplus.

The surprising negative effect of all these attempts was depression.

One instance of a depression following immediately after a period of budget balancing could logically be chalked up to coincidence. When the same sequence of events happens again and again, the pattern that emerges strongly suggests cause-and-effect.

Here is Prof. Kelton’s chart (taken as a screen-grab from the Youtube video of her lecture).

And here is a LINK to her Youtube video.